In a stroke of climacteric coincidence, archrivals Türkiye and Greece are scheduled for back-to-back national and presidential polls this month as an increasingly feverish political atmosphere dominates the two countries.

The outcome of the May elections, no matter which way they swing in either nation, will likely leave frayed ties untouched, save for inspiring more willingness for dialogue, according to experts who argued that the upcoming polls would mark a critical juncture for Türkiye’s relationship with the broader West mostly due to Greece acting at the behest of major powers.

At any rate, talks between Ankara and Athens are likely to resume the very next day, if the air of diplomatic positivity born in the aftermath of deadly disasters, the Feb. 6 earthquakes in Türkiye and the train crash in Greece, is any indication, two experts told Daily Sabah in an exclusive interview.

While Türkiye has been an arbitrator in setting the tone of Greek foreign policies in preelection campaigns up until the February earthquakes, issues with Greece have not been so prominent in Türkiye’s election agenda so far, observed Yücel Acer, author, member of SETA Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, and an expert of international law currently teaching at the Yıldırım Beyazıt University in Ankara.

For Acer, Greece comes up on Türkiye’s radar “mostly in relation to the United States and their defense collaborations and arming of the Aegean islands.”

Despite years of tension over maritime jurisdiction, energy exploration, continental shelves, airspace, the ethnically split island of Cyprus, and most pressingly, the status of islands dotted along their shared maritime border, Greece was among the first countries to convey condolences, send rescuers and offer aid to Türkiye following the devastating earthquakes that left over 50,000 dead, which Türkiye reciprocated after the train incident that claimed 57 lives.

Such grief that prompted mutual good wishes also gave relations a softer edge and pushed diplomats to take greater care in navigating their newfound optimism and even call for “bolder steps” to mend fractions on a new level, which Washington has also welcomed.

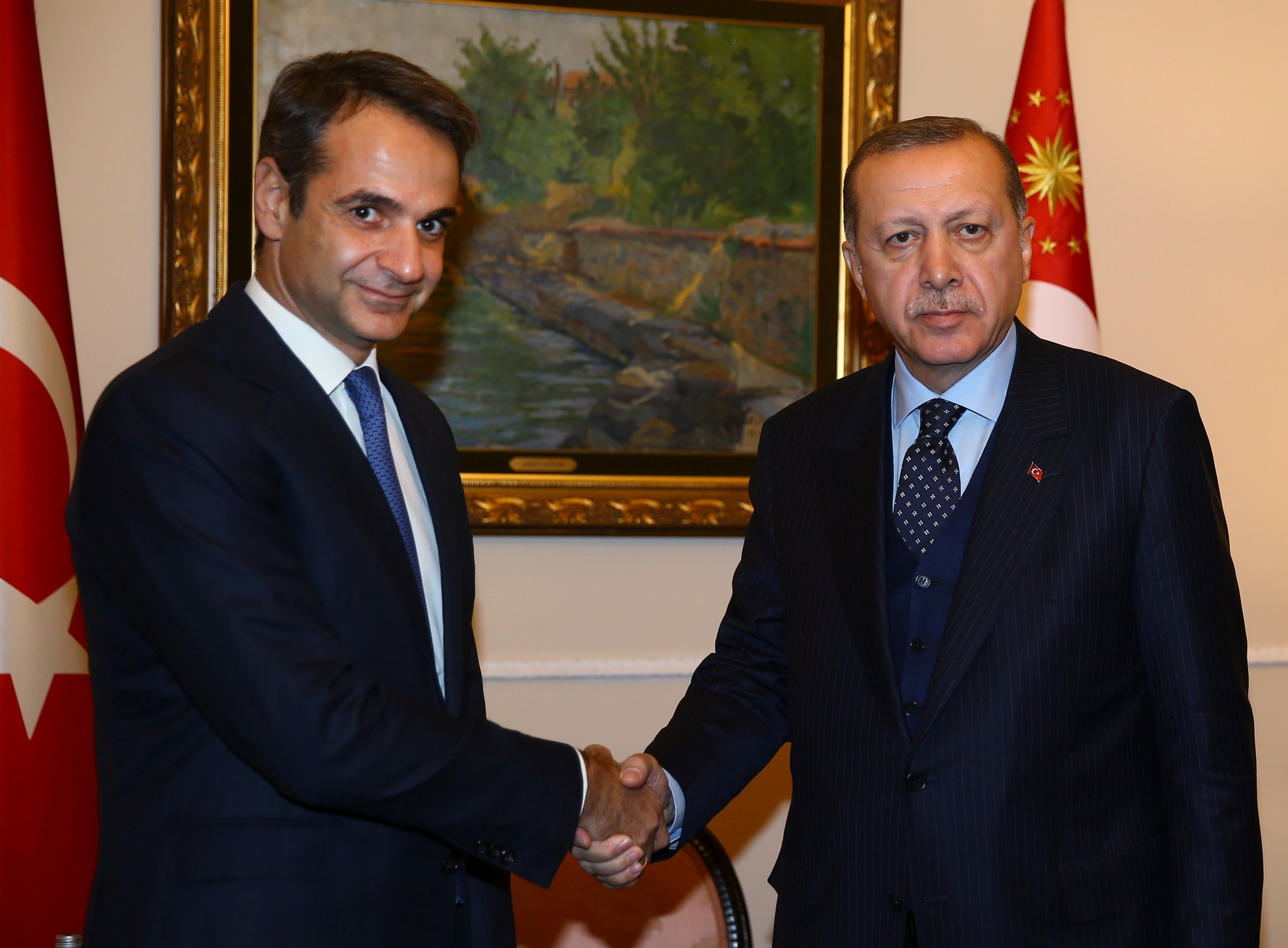

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threw out his vow to “never again” speak with his Greek counterpart Kyriakos Mitsotakis and accepted his condolences over the phone while their defense and foreign ministers met face to face, shook hands and expressed messages of amity.

In March, the fourth round of Türkiye-Greece Positive Agenda talks took place in Ankara and mainly focused on commercial ties. Still, according to Acer, all of this doesn’t constitute a direct contribution to a solution.

He believes it’s still unclear whether the current thaw could translate into a fully-fledged solution process after the elections because such dialogue is not the bedrock of progress.

Western demands

“It’s not reasonable to expect Türkiye and Greece to make progress after the election while Türkiye’s relations with the U.S. and the EU are still bad,” Acer said, attributing the “actual” reason behind the discord between the two nations to the “imperiousness” of Western powers.

Referring to Washington’s military buildup in Greece, the signing of a defense pact, sale of F-35 fighter jets, joint navy drills in the Aegean, as well as the strategic partnership Athens inked with France, among many other instances, Acer argued that Greece has “always dealt with Türkiye with the backing of major powers.”

“Both the U.S. and EU have extremely exaggerated demands from Türkiye, especially the U.S., with no regard for Türkiye’s national interests,” he said in an allusion to Washington’s refusal to cease supplying arms and training, right across the Turkish border in northern Syria, to terror organization PKK and its local affiliate, the YPG, a group that has led a bloody armed insurgency against Türkiye for over four decades.

Ankara’s counterterrorism operations against these groups and Daesh in northern Iraq and Syria have been a source of strain with Washington and other NATO allies.

Despite yielding a deal that effectively prevented a global food crisis last year, Erdoğan’s government is often criticized for maintaining diplomatic and economic ties with Russia while President Vladimir Putin leads his war of aggression against Ukraine.

“It’s not the Turkish government responsible for spoiling Türkiye’s relations with the West but these excessive demands,” Acer said.

However, according to an Istanbul-based Greek journalist, Washington is balancing a policy of equal distance to Türkiye and Greece.

“Diplomatic sources say the U.S. is preparing the ground to start the dialogue between the two countries after the elections, first on low-level political issues, then on major problems,” Vana Stellou told Daily Sabah. “Washington shapes the environment depending on its interests and the country it’s dealing with. The American establishment doesn’t want Türkiye to leave the West.”

Stellou believes the U.S. estimates negotiation conditions to become more accessible if Erdoğan clinches the May vote, regardless of whatever government takes over Athens.

“The important thing is that the positive momentum created by the disasters continues,” Stellou noted, calling for a lasting policy of good neighborliness between Türkiye and Greece.

Policy changes

As for the scenario where Erdoğan’s opposition, helmed by 74-year-old former civil servant Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu who is rallying a six-party coalition promising to undo Erdoğan’s policies in favor of more Western-oriented economic and social moves, comes out victorious on May 14, Acer argued that Türkiye would adopt a more “concessive” stance.

“Whether that would benefit Türkiye is a wholly different thing,” he noted. “That has been the opposition’s attitude so far, that they would ‘fix’ ties with the U.S. and the EU, but if they win, I don’t want to consider that they would compromise on Türkiye’s interests.”

He stressed that Türkiye has “long gone past the point of doing the U.S.’ bidding in everything” and contended that “reversing” that policy under the opposition government “would not yield progress.”

Erdoğan’s foreign policy will remain unchanged if he keeps his seat, as he has “always been determined to maintain a firm policy to protect Türkiye’s national interests,” according to Acer. “Regardless of what the U.S. or any other major power does to Türkiye, no one can expect any compromise from Erdoğan in either the Aegean or Eastern Mediterranean,” he said.

Odds of war

Turning to Mitsotakis’ chances of reelection, Acer noted that Mitsotakis’ conservative New Democracy party was holding onto a slim lead over the leftist Syriza party, despite growing pressure on his government over the railway crash, soaring inflation, and food prices, a wiretapping scandal, and scandals of Greek MPs of European Parliament, among other issues.

“As a Greek premier who has advanced his country’s relations with Western nations, especially France and most recently Germany, Mitsotakis is likely to stick to his policy of upping tensions with Türkiye in the Aegean, especially in arming the islands,” Acer explained.

The islands are meant to be demilitarized under the Treaty of Lausanne Türkiye and Greece inked in 1923, but it was documented last year that Greek troops were deployed on an island barely 8 kilometers (5 miles) off Türkiye’s southwestern shores.

Ankara has since slammed such “repeated provocations” from Greece, saying it was “frustrating our efforts for peace,” while Erdoğan warned Mitsotakis that Türkiye “may come suddenly one night if they keep acting out.”

The situation, also backed by the U.S., is a direct threat to Türkiye’s national security, according to Acer. “If after winning the vote Mitsotakis decides to continue this policy, I would say this, as the biggest source of tension between the countries, could create an actual skirmish,” he said.

Highlighting Mitsotakis’ “close relationship with the West,” Acer said he didn’t think the Greek premier would be “so concessive” toward Türkiye, but he “could be open to resuming negotiations.”

“Still, it’s not possible to expect a solution. Nevertheless, maintaining bilateral ties is useful for Türkiye and Greece, and that’s what I expect after the elections,” he concluded.

For her part, Stellou doesn’t see an actual war breaking out in the Aegean. “Erdoğan doesn’t seek war with Greece,” she said. “Türkiye’s economy is so well-integrated into the EU that a war with Greece is outside its strategic plan.”

Türkiye enjoys expansive arms trade with the bloc, which totaled a record $4.4 billion in 2022 alone.

Political scales

Of the current climate in Greece, Stellou said the political landscape could not be easily mapped, and any follow-up moves would take time, notably pointing to infighting among opposition parties over the prime ministerial post and partners in a possible coalition government, not unlike the quarreling in Türkiye’s six-party opposition bloc over similar worries.

According to Stellou, the May 21 nation election is the first time analysts have been unable to predict the outcome and can only assess that the first round will, in all probability, not produce a lead or self-reliance, paving the way for a second round on July 2. Türkiye also faces a presidential run-off on May 28 if no candidate secures the majority vote.

Stellou, too, conceded that the election results would reflect the anger in Greece. “But the Greeks have a short memory and will vote by what’s in their pockets,” she said, drawing a parallel with Turkish voters looking at a cost-of-living crisis that would likely influence their decision.

Highlighting another similarity between Greek and Turkish politics, Stellou said that Türkiye’s opposition alliance failed to offer “solid” ground due to deviations within, namely objections from the nationalist center-right party over conventional secularist Kılıçdaroğlu’s cooperation with PKK-affiliated Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), which is considered a kingmaker in the Turkish race due to the 10% support it holds among mainly Kurdish voters.

“Such heterogeneous alliances have statistically proven to be unstable, and Kılıçdaroğlu is more favored by circumstance than capability,” Stellou noted.

Recalling Kılıçdaroğlu’s promises of a Westward Türkiye, she said, “This doesn’t mean the West is a paradise. On the contrary, the West has many problems in its institutions, democracy, finances and politics. Just look at France, Britain, the U.S., Hungary or Poland.”

She also claimed that an absence of high-voltage public personalities in Türkiye’s central politics that could counter Erdoğan has not resulted in a “strong pole of interest with a political narrative capable of inspiring a change of government.”

“Whether Kılıçdaroğlu, who has never led a government, will be able to implement what he has promised is yet to be seen,” she said.

Source : Daily Sabah